A Dive Bar Punk Club, Zines, Bands, Suzy Rust, and Me: A Tale of 1980s Subcultural Boston

I still don't know why she disliked me so much. But it's all water under the Anderson Memorial Bridge.

Throughout history and especially before the Internet, people have relied on social connections to commiserate with others, share their troubles and maybe gossip and scheme a bit. Everybody needs a proverbial “bar where everybody knows your name,” preferably in real life and not in a sitcom. I encountered such a bar in the mid-’80s in Allston, a working-class neighborhood about two miles west of downtown Boston where I lived at the time, populated by sizable amounts of students, artists, musicians and immigrants. It was an age before Facebook and Twitter, even before MySpace. There were taverns like this in many neighborhoods, but this one belonged to our crowd. It was called Johnny D’s Sounds and Spirits, a modest dive bar at 85 Harvard Avenue. It doubled as a venue for punk, garage, and alternative local bands, many of them very alternative, ones that couldn’t by any stretch be called remotely commercial.

There were, of course, many other cool clubs throughout Boston at the time. Johnny D’s was far from the only game in town, but this was my local and it held a special place in the hearts of a couple of hundred folks, maybe more. Many writers, artists, musicians, hipsters of all types and even some relatively normal people shared my feelings about the joint, which gained popularity as a space where alternative-minded misfits, serious and not-so-serious artists could workshop new material in front of a sympathetic crowd that welcomed and was excited by their endeavors and their energy and recognized that this was all supposed to be fun.

By 1976, Boston’s local music scene was really starting to percolate as punk rock emerged from the tar pits. In 1981 the Propeller collective, a loose association of underground bands, many of them based in Allston, put out a highly influential compilation on cassette (recently re-released in a deluxe vinyl edition). Propeller, a sort of alt-rock Salon des Refusés of its time, had shown Allston’s musician/writer/graphic designer/used clothing shop entrepreneur and fashion adviser/misfit student/antique and collectible dealer community that the DIY ethic was not only a viable but deeply satisfying way to thumb your nose at the established powers that were, get your name known, and maybe make a few bucks on the side if you were very lucky. And as a bonus, you got to put some music out into the world!

For me, the Propeller cassette was the single most important recording that clued me in that something really interesting was going on in the local music scene. I don’t love every single track, but I still listen to the comp and certain ones on it are favorites of mine to this day.

Just like Propeller in ‘81, Johnny D’s and similar underground club scenes of the era showcased the products of rule breaking, poking the bear, rejecting the establishment, and most importantly, DIY creativity and vitality as young artists discovered the lengths and breadths of their talent and power to affect the zeitgeist.

Johnny D’s the bar was founded around 1969 (making it about the same vintage as the Johnny D’s Uptown restaurant/music club in Somerville, a completely unrelated venue it was sometimes confused with; that club closed in 2016). The era of the Allston Johnny D’s as a cool venue for bands, fun times and memorable shows probably lasted less than three years (1983 through early ‘86), perhaps no more than the average lifespan of many of the bands who played there, but it defined those years for me.

It was a modest working-class kind of place, dark and nondescript inside, with no stage except the floor. It was the age of $3 admissions and $1.50 beers. It sat on Harvard Avenue, a commercial block of small businesses: their neighbors were a fish store, a quirky copy shop, a Vietnamese grocery, a local bank, a couple of liquor stores, a newsstand, a larger but less cool established music venue called Bunratty’s (that’s another story), and so on.

In the early ‘80s, Johnny D’s was just another townie dive bar with a few regulars. It was way before the age of gentrification, and slowly, a few young musicians, writers and artsy types, drawn by the low prices and lack of pretension, began dropping by. An artist named Linda Cardinal a/k/a Miss Lyn, who published a fanzine called the Boston Groupie News, became a regular, as did musicians like Peter Dixon; Danny Lee, the drummer from the band Uzi; and underground writers Suzy Rust and Craig Federhen. A punk blues band called The Five began coming around after rehearsals.

As an article by Miss Lyn in the Boston Groupie News website circa 2006 relates, “As with any awesome dive bar, we were invading the space of the neighborhood old guys and townies who had been hangin' there for years but they were pretty open and friendly and let us in on their turf. Either way it was fun!”

A young guy named Rick Paige booked the shows. As he relates, “I worked there for a year or two before people started hanging around, I was just working in the kitchen, and I saw that (Johnny) had an entertainment license to allow for live entertainment. I was always like ‘Why don’t you use this, Johnny?’ And he was like ‘Oh no, bands just cause trouble.’ Then finally he called my bluff once people started hanging around, he was like ‘who are all these weird punk rock kids?’ So that’s how it started, he basically said ‘Why don’t you try a Wednesday night?’ And then he made more money – because the bar was dying, he wasn’t making any money just catering to the few old men who sat at the bar.”

Johnny D himself may not have been Allston’s answer to CBGB’s Hilly Kristal in terms of his personal musical tastes, but give him credit for openness. However, Rick Paige told me, “He made a point of making himself scarce (when bands were playing). He thought that if he was showing up he would scare people off or something.”

It snowballed. Johnny D’s soon became known as a venue that welcomed aspiring bands that played original material.

“The first thing I did to take over the joint was I started taking care of the jukebox,” Rick Paige said. “Johnny D had a jukebox there that people could change the records (in), he had total control over it. So I was like ‘Can I put records on?’ I had La Peste, Better Off Dead…I just put a bunch of records from my personal collection on there.

“People always said I did such a great job booking the club. At that time and place I couldn’t throw a beer bottle down Linden Street without hitting an aspiring rock star. It was easy. Everyone was literally right there, we were all on the same half-mile block, pretty much. It really was like a neighborhood bar for all the kids who lived in Allston. I don’t think we knew how special it was. It’s so weird when you look back (at) those days because we put a lot of living in those few years. You say like ‘Oh, gee, how did I see that many acts,’ or how did we do so much stuff in such a small, condensed time, but we did. We didn’t go that long.”

And in the spring of 1985, in an audacious and stimulating move, a few of the creative-minded regulars — Craig Federhen, Michael Gracia and Suzy Rust, soon joined by Peter Dixon — put out the first issue of a zine dedicated to the club: the Johnny D’s Liberty Guardian.

It was, in fact, a hyperlocal satire of a gossip-and-style magazine, focused on the people and happenings swirling around a single building. Hilarious, whip-smart and bursting with attitude, the project fascinated me from the get-go. The hippest zinesters, scenesters and punksters in town soon got on board with the JDLG (“Serving the Greater Riley’s Roast Beef Customer Area with all the news that fizzes,” per its tagline). In my mind it shares space for “classic magazine with the coolest writers and design, an essential read” with Spy, which started publishing around eight months after the time the JDLG, and Johnny D’s itself, were 86’d, much too soon, in February of ‘86.

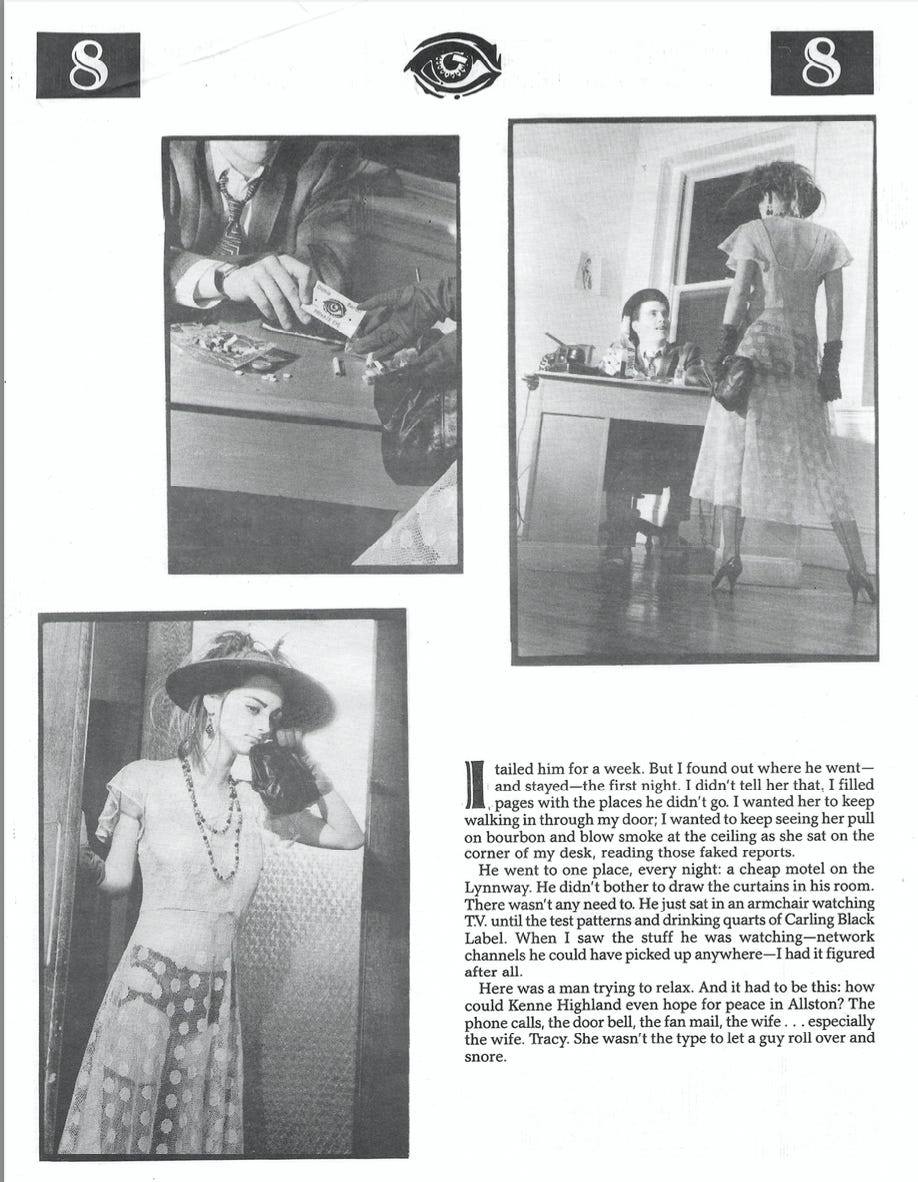

Among the writers, Suzy Rust stood out. She was a twentysomething woman of average height and build with dirty blond hair and a self-possessed air, who dressed in thrift-store chic (see below). She was witty and stylish as hell and extremely intelligent, possibly a genius, although only a few people in Boston seemed to know that.

Looking back, the JDLG had quite the subliminal influence on my own writing style. In particular I aspired to be as sharp, as witty, as fun as Suzy Rust in print. Bits and pieces of her various contributions to that brilliant little zine are permanently stuck in my long-term memory: for example (see above), “those three old ladies…watching the lights go out in Auto Part stores all along Brighton Avenue and murmuring the candlepin scores of their dead husbands” is a small masterpiece of concision. Then there’s the final sentences of her short story “Wilma Loop, Princess of Listlessness”: “At her boyfriend’s house, she will await the proper hour to arrive at Johnny D’s. And who knows what will happen there, in the one bar in Allston that’s better than nowhere.”

Suzy put out the JDLG along with her co-conspirator writer/editors Federhen, Gracia and Dixon with design and production by herself, Federhen, Jerry Channell and Kevin Amsler. Aside from an occasional guest writer, there were several obviously fake “contributors” listed that were pseudonyms for the staff.

There were never any actual ads in the zine. According to Rick Paige, “Johnny D paid for the printing. It was funny, after the first issue came out he came to me and said, ‘Hey, what the fuck, Rick? I'm paying for this magazine and all it does is make fun of the place!’ I said, ‘It's fine, Johnny. It's just loving ball-busting, you understand that. They love the place. People love the mag. They come in looking for it. It's fine.’ In his defense, he paid for the rest of the issues. If memory serves correctly, he may have been....er....slow to pay the invoice. But he did pay for the printing. I think.”

The only things I knew about Suzy I gleaned from the zine. She had a huge crush on Brian Jones. As did many in the scene, she had something of a history with alcohol and drugs, which she eventually wrote about in a one-off zine called The Dope (which was in part an informal postmortem on Johnny D’s; click here for a link to the complete issue).

To my dismay, however, for some reason — and I have no idea what that reason might have been — Suzy took an instant dislike to me and treated me with complete disdain whenever I encountered her (which was inevitably at Johnny D’s). Whenever I’d try to be nice and pay her a compliment about the Liberty Guardian, she’d respond with a withering insult and mocking glare. Yelp wouldn’t come into being for about 20 years, but if it had been around then Suzy would have given me zero stars for just existing. I happened to be putting out my own zine at the time (I ended up publishing four issues, as one did), and maybe she thought the thing was awful and she was entitled to her opinion, but really, what did I ever do to her? Maybe she was just a…mean girl?

Her mockery even extended to print: in the pages of the notorious punk zine Forced Exposure where she, for some misbegotten reason, covered a meeting of contributors to Boston Rock magazine that I and a bunch of other writers had attended in someone’s apartment, Suzy called me “a zero with bird shit for eyes.” (For the record, I’d describe the color of my eyes as grayish-greenish-blue, depending on the light.) Despite this, I couldn’t bring myself to hate her. Game recognizes game. She was the closest thing we groundlings had to the Joan Didion, the Nora Ephron, the Dorothy Parker of Allston.

Like a laser pointed at my weakest spot, Suzy’s contemptuous gaze seemed to target my most sensitive vulnerabilities and insecurities, and her mouth unhesitatingly followed suit. She saw me for who I really was, an inadequate pretender, or so I imagined. Many years later I emailed her and asked why she disliked me so much. She just mentioned something about being on a lot of drugs back then.

The Liberty Guardian wasn’t without its lower moments, like the catty “Aimee Mann visits Johnny D’s” fictional diss in the first issue back when ‘til Tuesday was riding high on MTV and certain members of the music community were more than a bit consumed with jealousy of them and Aimee in particular, and similar snipey remarks aimed at the Del Fuegos (who appeared in a TV ad for Miller beer in 1985 that totally destroyed any local or alt-rock cred they might have had up till then; of course, these days such a move wouldn’t merit a second thought from anyone). Youthful insecurity and frustration with one’s life up to that point leads to jealousy and sophomoric mockery of other, more successful people based on projections of their public persona or surface images in the media, suitable for a parody or standup routine which usually doesn’t correspond to the usually much more complicated and subtle actual person (and yes, back then I was occasionally guilty of this too). Ultimately it just makes you look petty and small, but in the best case scenario one learns from such early mistakes and is eventually able to identify more appropriate candidates to publicize as the true forces of darkness and leave people like Aimee and Dan Zanes alone. On the other hand, they took great care with the fiction, interviews, concert reviews, art, the satirical fake-gossip page (titled “Rumors, Lies & Slander”) and everything else they published, and applied proper OCD focus to proofreading; it warms my heart that they always spelled “fluorescent” correctly.

The graphic below ran on the back page of every issue of the Liberty Guardian, with variations for club listings (“And don’t forget Organ Donor Night every Thursday!”). I can’t believe that nobody ever corrected the mistake in the club’s address — their one glaring proofreading error — it was on Harvard AVENUE, not Harvard STREET (there is a Harvard Street in Boston, but it’s in Dorchester); but then, I only caught that myself while re-reading all the issues in January 2025. (By the way, Rick Paige never actually performed there — any listing mentioning him and his backup band of the moment was a placeholder for dates that hadn’t yet been booked.)

In the Liberty Guardian, local bands like Black Cat Bone, Moose and the Mudbugs, the Pajama Slave Dancers, the Five, and the Beachmasters were the equivalent of Aerosmith, Dire Straits, Foreigner, or the Rolling Stones. No offense meant by “local bands,” by the way, as everyone has to start somewhere, people love to see their friends on stage, and many combos who hit the Johnny D’s stage/floor were highly respected and went on to bigger things: Throwing Muses (“Rhode Island’s answer to The Slits,” per a review of a show on June 27, 1985), the Turbines, Scruffy the Cat, Salem 66, the Dogmatics, Volcano Suns, the Prime Movers, the Mighty Mighty Bosstones to name a few. Garage rock, art punk, and loud, pounding punk blues were the rage. Street-level creativity ran rampant. Anything even a bit slick or seeming to aspire to the Top 40 or WBCN’s heavy rotation was fair game for mockery in the zine, as was, inevitably, Mike Barnicle’s column in the Boston Globe. Even the DJs at WMBR, MIT’s hip extreme-left-of-the-dial college radio station, weren’t immune to the occasional zing from the editorial board.

So with all that going on, why on earth did the place close in early 1986? “Well, we actually made him (Johnny) enough money that he wanted to turn it into a nice restaurant,” Rick Paige relates. “He always had a dream of having a nice Italian restaurant, regardless of the fact that he wasn’t set up to run a fancy restaurant. He was a townie. His brother-in-law (said) ‘We could make a really nice, fancy restaurant here.’ Literally, Johnny D said ‘With tablecloths and shit.’ So what are you going to say? We’re making money, you can do your dream, you know. And literally I don’t think it lasted three months.”

The short-lived bistro was called the Allston Ale House.

“I walked in a few times,” said Rick, “and it was just absolutely dead, right at noontime or 2 o’clock. It looked exactly like it looked before I started doing bands. There were no tablecloths. I think in retrospect (Johnny) probably would have preferred not to have gone that way, but again, what can you do when the guy says ‘I want to change.’ Here’s another thing: he had a kid at the time who was just starting middle school or grade school and he was like ‘I don’t want my kid to have to put up with other kids telling him hey, your dad runs a punk rock club.’ I was like, why would he care?”

“Actually,” I said, “that sounds like a pretty cool thing now.”

“Exactly. He had funny ideas. He was a great guy, I got along with him great, I actually really liked working the kitchen for him, but he didn’t have a great business sense.”

Johnny D, a/k/a John Mathew DiGiovanni, died on October 11, 2021. He was 79 years old, which meant he was only in his mid-40s during the glory days chronicled above (although he seemed older to us at the time). Here’s a link to his obituary, which states, “Born and raised in Roslindale, he was a longtime resident of Brighton” and was an Army vet.

As for Suzy Rust, she eventually returned to the St. Louis area, where she was originally from, and in 2007 was featured in an article in the Riverfront Times that named her as a thrifter and collector who maintained a website called luckyfindgazette.com, which is not currently online. She told the reporter, “When I lived in Boston, I used to write for punk-rock fanzines, and I put out three of my own. This is sort of a continuation of that. But I'm not a punk rocker any more. Now I just listen to Dean Martin.” She was then known as Suzy Crancer or Suzy Rust Crancer (her married name, I assume).

God knows what she’s doing today. But Suzy, as far as I’m concerned we’re cool. I hope you’re doing well.

I’ll leave you with this excerpt from an interview with Rusty Zapata, bassist for the band Black Cat Bone, in issue #6. Ah, to have been in Allston in the ‘80s! It hits different now.